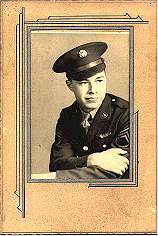

Service photo in uniform, indicating the rank of Sergeant

Charles P. Gyllenhaal was inducted on June 6, 1942, and honorably discharged on January 6, 1946. He served as a Technician, 4th Grade, reaching the rank of Staff Sergeant. He was assigned to Detachment X, 4025th Signal Service Group. At first he trained as a radio operator and aerial gunner on a B-17 bomber, but later he served as Message Center Chief in New Guinea and the Southern Philippines. He received the following decorations and citations: Good Conduct Medal, Meritorious Unit Award, Philippine Liberation Campaign Ribbon with 1 bronze star, the American Campaign Medal, the Asiatic Pacific Campaign Medal with 3 bronze stars, and the World War Two Victory Medal. For more information see his Enlisted Record and Report of Separation, Page One and Page Two.

The paragraphs below were abstracted from The Gyllenhaals of Alnwick Road, a family history by Charles Pendleton Gyllenhaal (1919-1989). The selected portions deal with some of his World War Two experiences in the U.S. Army. Most of the pictures come from his wartime scrapbooks. The text and pictures were selected by his grandson, David Nils Gyllenhaal, age 10. (David's father, Charles Edward Gyllenhaal, helped him write the captions.)

The war was part of our lives even before the Pearl Harbor attack resulted in the U.S. becoming involved. Bryn Athyn had formed a civil defense unit, armed with shotguns. Some of us joined and learned to shoot a little and march a lot. But it was quite uncertain if the U.S. was ever going to enter the war.

The cover from one of Charles Gyllenhaal's wartime scrapbooks

In early February I began training as a radio operator-gunner on B-17 bombers in an airfield that was strangely placed in a valley surrounded by mountains in Idaho. The commanding officer of my unit, part of the time, was Jimmy Stewart, the movie star. He was popular with the men because he brought lots of pretty starlets up from Hollywood. They put on camp shows for the flyers.

In March I wrote from Idaho that I couldn't go overseas on an air crew because I had flunked the vision test. That may have been the reason, but I was also considered a "jinx" by some. I washed off one crew when I got the mumps and the crew perished not long afterwards when shot down in Europe. I survived a crash landing of a B-17 bomber and was on another one that went out of control and almost didn't make it safely to the ground. In any case I was reassigned as an instructor and took new radio operators up to learn the ropes. Several times Jimmy Stewart was instructing the pilot on the same plane.

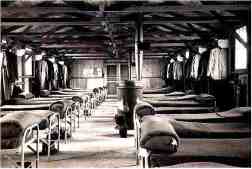

One of his barracks, somewhere in the western U.S.

I kept this up for several months. One morning they failed to wake me up in time to take a young radio operator on his first training flight. The plane hit one of the mountains. I was assigned to take his body to his home in Mississippi and got leave to go home afterwards. Mother's diary notes that I had taken a body home, but apparently I hadn't told her the circumstances.

Rationing was in full swing. The diary [my mother kept] says "asked for more gas--turned down." They were having air raid drills in Bryn Athyn. Extra heavy curtains were made for the whole house. When the siren went off they would draw the curtains and turn off the lights. They took these drills very seriously, Anne remembers. They were often afraid it might [be] a real air raid warning. Mother wrote to her sons religiously and sent us everything she thought we needed, from tobacco and talcum powder to socks and soap. She also sent us Time and Life magazines keeping track of the many address changes endlessly. She wrote faithfully and it appears from the diary that we wrote home often. Perhaps we did this to keep her from worrying.

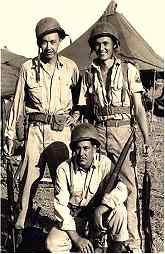

Charles (top left) in battle fatigues holding a carbine, with two of his buddies

Her sons were eventually spread all over the world and were almost always on the move. She kept track of them with pins on the map. She followed the events of the war by reading the New York Times from cover to cover every day. She always had the Lowell Thomas news broadcast on the radio. At this point in the war [the fall of 1943] it seemed to many that it would go on forever. I remember that I seldom, if ever, thought about what I might do after the war. Things were looking up in Europe but the end of the war in the Pacific seemed years, if not decades away. None of us were made to be soldiers and life was frustrating. It was frustrating too for everyone at home....

When our ship finally found land it headed up a river. It was in Papua, New Guinea. It was a staging area for further north, behind the combat troops, to set up communications. New Guinea was by far the most interesting place I visited. Heading up the river there was dense jungle on either side. When we landed and were transported to our area we found ourselves surrounded by jungle with thousands of birds and trees. On the ground were flowers of all colors. I assume that some of them were impatience, my favorite flower. They originated in New Guinea.

One day a British sergeant and several American officers stopped by our camp and asked if anyone wanted to go into the interior of the island to see a native celebration. The British sergeant had been invited by the chief and the natives wanted some Americans to come along. I was the only one in the outfit interested! Everyone else said it was too hot.

We went by jeep on a jungle trail about 35 miles inland. We came upon a large village of straw huts with a clearing in the middle. The natives were assembled in front of their "king" who was dressed in a fantastic costume of many-colored feathers. His two wives were by his side, dressed demurely. Shortly after we arrived there was a wild dance by many natives, all male. They were beautifully attired with colored feathers. They were celebrating the return of some of their fighters who had engaged the Japanese further north. They fought alongside the British units.

Modern tribesmen from Papua, New Guinea, wearing brightly colored traditional dress

After several weeks we left the area and headed north on a landing craft which had engine trouble. The rest of the convoy outran us. We went up the coast slowly and very close to the shore for safety. The scenery was exquisite. After two weeks we reached Leyte, the Philippines, fortunately after all the fighting was over.

My outfit arrived in Manila in the Philippines. The city had almost been totally destroyed by bombings. There were many ruined buildings but very few people. The Japs were still in parts of the walled city in the center of Manila. We set up a communications center for American forces in a building that was half in ruins.

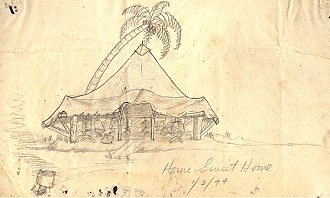

A sketch of his tent somewhere in the Philippines during January of 1944. His job was to translate coded messages sent by the Japanese.

Several of us in the center decided to do some exploring. We borrowed caps from some officers to get through the lines around the walled city. (Only officers were permitted.) We found a ruined bank and in the basement lots of money. Unfortunately the money was printed by the Japs for use in the Philippines and other countries and was considered worthless. We took it back to our living quarters and organized it into packets of about 35 different pieces. We sold them as souvenirs to the sailors who were coming off the ships for one day shore leaves. The packets sold very well.

An example of the "invasion money" printed up by the Japanese, found in a ruined bank.

Soon when our signal corps jobs began taking too much time, we organized some Philippino boys to do our selling. They were surprisingly honest. I made enough to buy a brand new car after the war. (I still have some of that worthless money, if anyone is interested....)

Charles (second from right) in Manila with Bryn Athyn friends Bill Brown and Louis Carswell, holding newspapers on V-J Day. Newspaper on left reads "JAPS PUT HANDS UP," and newspaper on right reads "JAPAN QUITS."

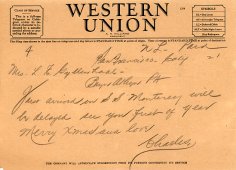

The Monterey landed in San Francisco on Christmas Eve. It was foggy and the first hint we had that we were near San Francisco was when we looked up and saw the Golden Gate bridge above us. About three thousand troops were told they had to stay on board until after Christmas. (The city fathers didn't want us in the streets.) We rioted. The national press came aboard and took a picture of some servicemen they had coached to look forlorn. We were lying in our bunks. It was the first time my picture was in hundreds of newspapers from coast to coast. (The second time hasn't happened yet.) I finally got home Jan. 10.

|

|

LEFT: Charles lying on his bunk on the U.S.S. Monterey, on Christmas Eve of 1944. (Second bunk from the bottom, reading a book--note the Christmas tree.) RIGHT: A telegram sent to his mother on Christmas Day from San Francisco.