Gyllenhaal, Leonard, brother of Johan Abraham Gyllenhaal, born Dec. 3, 1752 in Bråttensby (Älvsb.), died May 13, 1840 at Höberg, N. Vånga (Skaraborg). Corporal in the Adelsfana [the cavalry force of the nobility] Nov. 15, 1765, livdrabant [Life Guard] Apr. 22, 1773, lieutenant in the army Oct. 22, 1777, captain there May 20, 1789, resignation as major Dec. 18, 1799. Entomologist.

Married Jan. 4, 1788 in Synnerby (Skaraborg) to Anna Hård af Torestorp, born July 25, 1763 at Kilagården, V Gerum (Skaraborg), died May 28, 1845 at Höberg, daughter of Lieutenant Ulrik Gustav Hård and Baroness Eleonora Margareta Fleetwood. Gyllenhaal was a student at Skara elementary school and upper school 1759-68. He himself recounts that he "had an interest since childhood in natural history." In that science the schoolboys of Skara received no instruction, but like several others who were later known as Västergötland scientists, Gyllenhaal laid the groundwork during his school years for that interest. Together with his brother Johan Abraham Gyllenhaal, Anders Dahl, Lars Brandelius and the brothers Adam and Johan Afzelius, he undertook excursions in Skara's surroundings and gathered collections of plants, insects, mollusks and minerals.

According to previous information, he should have become a student in Uppsala in 1769, but he does not appear in the register of students. Letters from himself and from his brother, however, indicate that Gyllenhaal that year obtained instruction in the natural sciences from Linnaeus, and got to know his pupil C. P. Thunberg. From an economic viewpoint, this academic track was insecure, and enthusiasm for Linnaeus' science had begun to weaken with the public towards the end of the 1760's. Besides, family tradition required that one of the sons become a soldier. Therefore, Gyllenhaal left Uppsala after some time and in 1769 took a position in the Adelsfana in order to work his way into the Life Guards four years later.

He used the long periods of leave from military service to continue his studies on his own. In 1771 and 1772, he followed his brother on his trips to Västergötland and Bohuslän. At the topographical society founded on Olof Knös' initiative in Skara, Gyllenhaal around this time left treatises on seashells found in the area of Uddevalla and plants collected in the home parish of Vånga. Abraham Gyllenhaal tells in a 1773 letter to the academy secretary Wargentin, that Gyllenhaal studied the Academy of Science's documents with the same eagerness as a theolog does his Bible.

Gyllenhaal had for several years now been the farm foreman and chief farmhand on the family estate, Höberg, [see photos below] but in the beginning of the 1780's he began, according to what he reported to his brother, to feel "down-hearted about laboring under restrictive management almost like a domestic servant." Faced with the son's threat to move away from home, the father in 1784 allowed him to take over the property on lease. Now that Gyllenhaal had become his own master, he began, with the help of capital borrowed from his brother, to modernize the running of the estate, and became an avid agriculturist for the rest of his life. He devoted himself to experimental cultivation of, for example, corn and various fodder crops, and played an important role in the shift labor in Skaraborg's province. In order to dry out the Sjögerås bogs and lower the water-level of Rösjön, he had canals dug, which required thousands of man-days of work. Höberg became a model farm, and its owner held the presidency in the province's rural economy association 1812-17. For his contributions as an agriculturist he became a knight of the Vasa order. After the deaths of his brother and his father-in-law, Gyllenhaal received working capital and raised Höberg's acreage to more than seven mantal [an assessment unit of land]. From 1813 to 1820 he was a one-third owner of Klosters factory in Husby (Kopp.). Good years and good sense made him a wealthy man, known for giving help to the needy without any fanfare.

From the age of thirty, Gyllenhaal was a convinced Swedenborgian. The new church had a strong foothold in Västergötland, and among the better-known supporters was Gyllenhaal's maternal uncle, Paul Wahlfeldt. The latter was for many years a lector in Skara. Towards the end of the 1760's he had to answer in the university court for Swedenborg's errors in speech and writing. In a letter to his brother, Gyllenhaal tells how their uncle in his last days rejoiced in the decline of his body, and how shortly before his death with a smiling expression he informed those standing around him that his pulse was stopping. His death convinced his nephew that there was another world, and that the transition to it was easy and happy for one who had not bound his senses to the material.

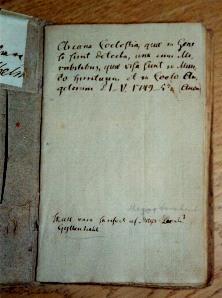

Gyllenhaal translated and with his elegant handwriting made copies of

Swedenborg's work, and supported the printing and free distribution of the master's work [see photo below of one of Leonard's signed handcopies]. He wanted, as he writes to a like-minded person, to by every means "ensure the public's access to such books, which contain unadulterated truth." He was never a supporter of the kind of fanatical Swedenborgianism which J. G. Halldin and C. F. Nordenskjöld represented, but belonged to those moderate and pious men who in 1796 formed the society "Pro Fide et Caritate." As a result of his scientific research, his religiosity did not force its way in, but as is clear from his letters and the evidence of contemporaries, it gave his general view of nature a quality of insight and contemplation.

For military service Gyllenhaal entertained a cool interest. He saw it as a hindrance to agriculture and entomology. The duty of the Life Guard corps at that time was to stand guard at court, and the various detachments' annual service was short. When Gyllenhaal in 1799 on account of an increased guard around the crown-prince had to stay in Stockholm beyond schedule, he asked for retirement. He seems to have visited the Parliament chiefly to have occasion to meet fellow-believers there, and to judge from his letters, he looked at the political disputes and revolutions of the time from the perspective of eternity.

Gyllenhaal's interest in natural history had originally applied to the entire scope of the discipline. In a letter to Linnaeus in 1775 he tells about an insect collection of 1,300 to a large extent unidentified species, which he gathered in western Götaland, but it was in 1783 that he first resolved to devote his scientific energy exclusively to entomology, encouraged by, among others, his brother and Thunberg. He had a pavilion, "The Flyhouse," built in his garden, which he fitted out as a museum and workroom [see photos below]. His insect collection comprised, when it was deposited in 1836 with the Scientific Society in Uppsala, 400 boxes filled with carefully prepared and identified creatures. B [Brandelius?] states that he spent a significant part of his life assembling the collection, and that he put up for the acquisition of insects at least 4000 riksdaler banko cash. The collection was taken over in 1866 by the university's zoological museum. Gyllenhaal was in frequent letter-contact and exchange with Swedish entomologists, and several of the younger ones -- for example C. F. Fallén, J. V. Dalman, C. H. Boheman and J. W. Zetterstedt -- saw him as their teacher in the scientific method. In the summers they willingly visited Höberg to enjoy old-fashioned hospitality in a harmonious home, and endless entomological discussions. Boxes of exchange insects went back and forth across the land. Sorrowful remarks about flying creatures shaken to bits on the carriages are a common ingredient in their letters.

|

|

For several decades, Gyllenhaal received good advice and references to literature from Thunberg, but the correspondence seems to have ceased when the latter fell out with what he called "the damned Västergötland league," that is to say Gyllenhaal's friends the professors Johan and Adam Afzelius. The only foreign journey Gyllenhaal undertook was to Copenhagen, where he visited entomologists and studied collections. Gyllenhaal was in communication for many years with the French general and beetle specialist P. Dejean and the Finnish count C. G. Mannerheim, as well as the mild-mannered specialist in English bees W. Kirby. In an 1803 letter Gyllenhaal complains that his only "insect companion" in his home province, the magistrate C. H. Pentz in Alingsås, died. Later he received good compensation for this, when fellow-believer and entomologist C. J. Schönherr settled down at Sparrestad, situated not far from Skara.

On his Insecta Suecica, in which he classified and described Sweden's beetles, Gyllenhaal labored a good 30 years, and he had to pay for its printing himself [see photo below]. It was rewarded with the Academy of Science's gold medal, and made him an internationally known coleopterist. His remaining output was on a smaller scale: entomological reports and monographs. He contributed further with species descriptions in the works of Fallén, Dahlbom and Schönherr. In the transactions of the Academy of Science he participated only one time, and he never became close to the academy. Gyllenhaal's style in connection with scientific things is marked by a dry precision, and his descriptions by a completeness never before equalled. He introduced new rules for insect identification and new foundations for the classification of beetles. Among the acknowledgments he experienced, he placed special value on his election to honorary membership in the Société Entomologique in Paris, which was extremely sparing with such recognition.

"The Flyhouse" also contained Gyllenhaal's library. The printed list of this extends to 98 pages. It contained, besides natural science, philosophy, biographies and Swedenborgiana, a multitude of rare printings from the 15- and 1600's, as well as one of the most complete collections of dissertations from Swedish universities. Much of it can be presumed to be an inheritance from his father, but the collecting had been continued by the son well into the 1830's.

Gyllenhaal was a tall man, widely known for his vigor. In 1783 he had been forced to amputate the toes of one foot after being frostbitten, which made his gait stiff and halting. During the last three years of his life he was nearly blind. He retained his mental faculties to the end of his days. Gyllenhaal's grandson Anders Leonard emigrated to the United States, where his descendants held fast to their forefather's faith, and worked as active members and teachers in the New Church.